Author – James Watson

Publisher – Weidenfeld and Nicolson (Penguin for later editions)

Date – 1968

Rating 5/5 (for being classic – but 1/5 for its depiction of Franklin)

Background

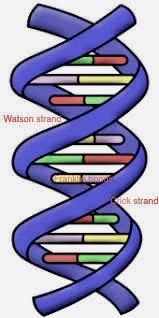

As a geneticist, the discovery of the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is probably the greatest achievement in my field to date. This book is written by one of the scientists who was instrumental in the discovery and chronicles his involvement. For those who are not aware, DNA is made up of repeated units joined together by phosphate groups in a double helix, like a staircase. The steps of the staircase are made of four types of chemical which occur in a sequence. Understanding the structure of DNA has allowed scientists to work out its function and how it is able to code for amino acids and thereby proteins.

The story starts in 1951 when James Watson, a 23 year old American post-doctoral researcher, met Francis Crick, an eccentric 35 year old Brit at Cambridge. The two would become household names for their discovery of the structure of DNA and thereby allowing the understanding of its function. It amazes me that it wasn’t until 1944 when DNA was really starting to be considered as an important molecule. Prior to this, all efforts were put into understanding proteins which were seen as much more complex and exciting than a simple molecule made up of only four component parts. How could such a simple molecule be of any relevance? Erwin Schrodinger wrote ‘What is Life’ in 1944 where he was a pioneer of the theory that genes were key components of living cells. At the time, genes were not understood and it was generally accepted that genes were specialised proteins. It was, indeed, Schrodinger’s masterpiece that led to Crick’s defection from physics into biochemistry and, ultimately, genetics. Experiments in the US by a bacteriologist, O.T. Avery, in 1944 were the first to suggest DNA as the main player in heredity as he transfected bacteria with DNA from other cells and saw its dramatic action. As with all discoveries in the field, the gravity of Avery’s work wasn’t immediately appreciated.

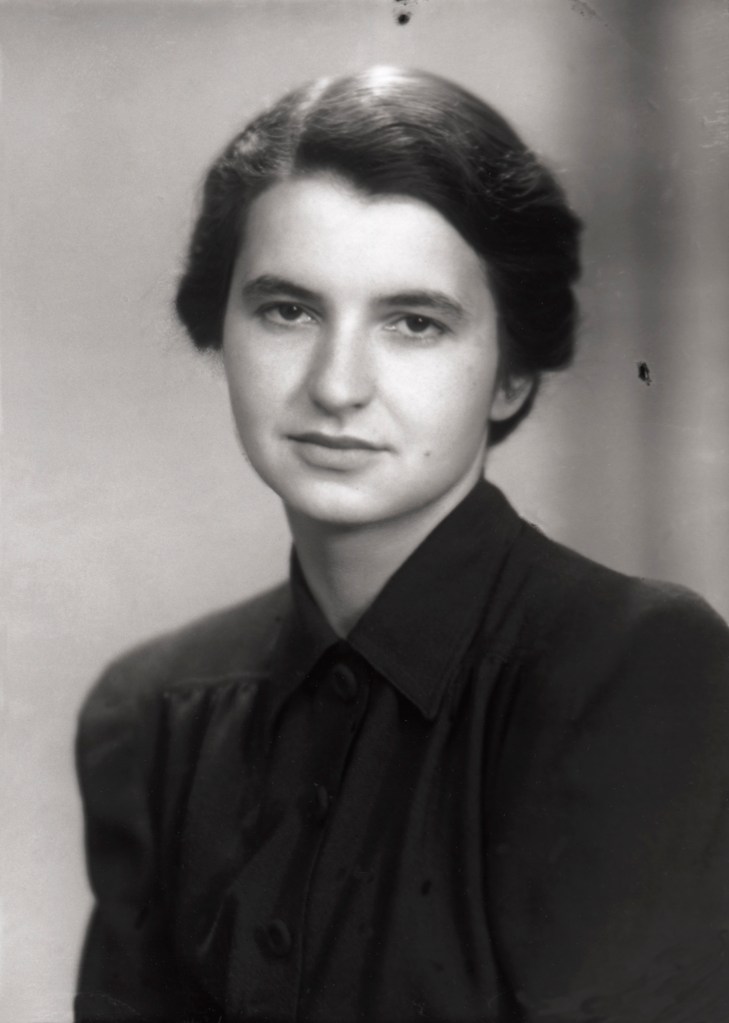

Franklin

Rosalind Franklin was born in 1920 to a British Jewish family in London. As a child, she was described as ‘alarmingly clever’ and actually left secondary school with a scholarship of £30 per year to attend university, which considering the time and attitudes towards female education, was astounding. She studied chemistry at Cambridge and eventually received her PhD in 1945. Surprisingly, her PhD thesis had been about the porosity of coal and her work went some way to develop better gas masks. After searching for jobs for “a physical chemist who knows very little physical chemistry, but quite a lot about the holes in coal”, she went to Paris where she began working with X-ray diffraction (shooting X-rays at a target and deducing by their displacement, what kind of structure it may be).

In 1951, she returned to England and worked at King’s College, London under the supervision of Sir John Randall. An important collaborator was Maurice Wilkins, who was already working on X-ray diffraction but was on holiday when Franklin arrived in 1951. Randall was, by all accounts, a pretty awful supervisor. He essentially gave Franklin the X-ray work along with a PhD student, Raymond Gosling, to continue looking into the structure of DNA. He did this without telling Wilkins that he was essentially kicked off the job. Of course, this unorthodox management technique did not go down well. Franklin and Wilkins had a famously fractious relationship.

When Franklin had finally had enough of Wilkins ego, she decided to leave in 1953 to continue studies at Birbeck College, London. It was at this time, that Wilkins presented the infamous ‘Photo 51’ to Watson and Crick. Franklin and Gosling had taken this photograph in 1951 but were yet to publish it. As Franklin left, Wilkins became Gosling’s new supervisor and Randall insisted all of their results were shared and DNA work remained at King’s, essentially, providing him with Photo 51. This photograph proved to be the talisman that spurred Watson and Crick on to crack the enigma. Although, they used many other techniques (namely molecular modelling which Franklin was opposed to), Photo 51 was certainly a large player in their discovery. Wilkins never made Franklin aware that he would show this photograph to Watson and Crick and reading this story does, unfortunately, smack of underhand tactics and inherent sexism. They did receive some credit, albeit inconspicuously, in Watson and Crick’s Nature paper as a footnote…

“having been stimulated by a general knowledge of” Franklin and Wilkins’ “unpublished” contribution.”

At the time, there was a rush to discover the structure. Linus Pauling, an American molecular biologist, had been working on DNA at the same time and had submitted a paper describing what he thought the structure of DNA was in 1952 but this was a triple helix and had the phosphate groups on the inside. He was an American and he did not have access to the X-ray diffraction photos which guided Watson and Crick who were in a rush to correct him and beat him to the structure. It is also said that Sir Lawrence Bragg, who pretty much invented X-ray diffraction and was director of the Cavendish laboratory in Cambridge was also pretty miffed that Pauling had beaten them to the discovery of the alpha helix structure of proteins some years previously. This gave Bragg the impetus to push Watson and Crick into understanding the structure of DNA before anyone else did. It should be noted that it was Franklin who first suggested the phosphate groups to be on the outside of the molecular in a lecture in 1951 where Watson was known to be in attendance.

Aftermath

Sadly, Franklin died in 1958 aged only 37 from ovarian cancer. Several other members of her family also suffered this condition. There has been suggestion that, rather like Marie Curie, her chronic exposure to radiation for her work may have predisposed her to developing the condition. There is also the possibility that she was a carrier for cancer-predisposition mutation, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2, which are known to occur at much higher frequency in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. This would be a rather cruel twist of fate if true. Nonetheless, she lived a short but very fruitful life in the scientific community. In her personal life, she never married or had children and was seen as somewhat of a recluse.

Remarkably, Watson, Crick and Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize for Physiology in 1962 but Franklin was not mentioned. Watson has suggested she should have been included but the Nobel committee have said they do not confer post-humous awards so the fact that she died in 1958 seems to have precluded her to be solidly admitted to the science hall of fame. She is often forgotten but is quite clearly one of the most important women to have ever existed. Later in her career, she worked on viruses and DNA’s intermediary, RNA, for which earned her successor, Aaron Klug, the Nobel Prize in 1982. It would be nice to think that, had she lived to see this, then she would be been rewarded as she deserved. A lecturer of mine used to teach genetics and refer to the two complementary strands as a ‘Watson strand’ and a ‘Crick strand’ so I wonder if there is some way we could acknowledge Franklin in this way. Maybe the ‘Franklin bonds’ to describe hydrogen bonds between bases, which would tell all that the discovery, most probably, would not have occurred had she not been involved.

Unfortunately, her description in the book is clearly weighed down with the sexist rhetoric of the time. Although her scientific knowledge and acumen is acknowledged, Watson comments on her being hard to work with and not caring about her appearance. Why should she care about her appearance when she is hard at work making a pivotal discovery?

“By choice she did not emphasize her feminine qualities. Though her features were strong, she was not unattractive and might have been quite stunning had she taken even a mild interest in clothes”

It is also sad to read that they referred to her as ‘Rosy’ which she hated. She wanted to be addressed as Rosalind and made this clear to all she met. Whilst Watson, Crick and Wilkins may have all the glory, I don’t think they can deny the way they spoke about Franklin was not how anybody should be treated. It is upsetting that Watson refers to her as ‘Rosy’ in the book throughout and you get a general feeling of disrespect whenever she is discussed.

In summary, I would recommend you read this book even if you have no understanding of genetics. The book is mainly about the discovery itself and the social impact it has had. It is a tale of caution to all men and their egos. People should be valued by their contributions equally and each contribution should be acknowledged as having arisen from a particular source. Trying to gazump others and stealing the limelight will only make you less popular in the long run.

Has anyone else read this book? What would you say about Watson’s depiction of Franklin? Was it excusable of Wilkins to commandeer her work and ultimately gain from it (he was working on it before her I guess)?